Considered the father of modern American architecture, Frank Lloyd Wright’s work is dotted across California with the greatest concentration of buildings located in Los Angeles. Six houses are here in various condition: the-open-to-the- public and city owned Hollyhock House and its under-restoration Residence A; privately owned residences include Pasadena’s La Miniatura (the Millard House), Brentwood’s Sturges House, Hollywood’s Storer House (exquisitely restored by film producer Joel Silver in the early 2000s, he currently owns Wright’s Auldbrass Plantation in South Carolina), the highly visible Ennis House (on the left) in Los Feliz and the Stanley and Harriet Freeman House above the intersection of Highland and Franklin Avenues.

Their historic significance and pedigree is almost unmatched: Wright’s architecture was truly original and genuine, certainly not a revival, and always his own. All are exquisite landmark residences requiring special care. Hollyhock House was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2019, the only such site in Los Angeles. Due to the construction of Hollyhock House (from 1919-1921), one could argue that Southern California’s modernist movement also got a huge jumpstart, as the project famously brought architects Rudolph Schindler and Richard Neutra to Los Angeles. Lloyd Wright (FLW’s son) eventually became an important architect here as well; his work remains highly influential and includes the famed Wayfarer’s Chapel in Rancho Palos Verdes and the intriguing Sowden House on Franklin Avenue.

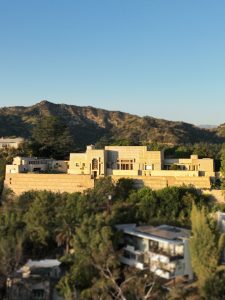

The city of Los Angeles owns and maintains the Hollyhock House (4800 Hollywood Blvd. – on the right) within Barnsdall Art Park. It was a gift to the city in 1927 from oil heiress and theater producer Aline Barnsdall who commissioned Wright to design a hillside complex that was to include a personal residence, two guest houses, a theater, a reflecting lake and shops lining Hollywood Blvd.

Wright and Barnsdall had crossed paths in Chicago and she was the one who eventually brought the architect west. Due to a number of factors, including cost overruns, Wright’s attention to building the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, Japan and Barnsdall’s decision to disband her theater group, only the main house, garage and two guest residences were completed. Residence B was demolished in 1954; Residence A is currently under careful restoration by the city’s Project Restore and will reopen to the public in 2023.

To this day, Frank Lloyd Wright remains a pivotal influence on residential architecture. He was the first to devise the open plan living room and was a forerunner of expanding the relationship of a house to the external natural world. At Hollyhock House, his design intent was to create a half house, half garden. Each interior space has a corresponding exterior space connected by loggias, colonnades and/or terraces. A stylized hollyhock flower motif is found throughout the property on decorative concrete planters, on columns, on the roof finials and within the stained glass windows. Reportedly, the stalk flower was Barnsdall’s favorite.

Hollyhock House’s most recent restoration, completed in 2014, fixed perennially leaking roofs, repaired seismic related damage and brought the design back as close as possible to Wright’s original. Remarkably, the dining room table and chairs—also sporting a hollyhock motif—remained with the house. The custom living room furniture, reputedly put in storage and lost, was remade in the late 1990s following Wright’s design. He called the house an example of California Romanza, an architectural style appropriate to the temperate Southern California region.

From Hollyhock House’s west lawn, the Mayan Revival style Ennis House (2607 Glendower Ave. – on the right) is clearly in view, perched dramatically on a Los Feliz hilltop. The striking temple-like construction consists of an estimated 27,000 to 40,000 hand- made concrete blocks. A novel material in the 1920s, the blocks were made from decomposed granite culled from the site. The home’s dramatic appearance has made it popular with filmmakers, most notably in 1982’s Blade Runner.

The interlocking blocks create drama from the monumental exterior into the well-proportioned interior spaces. Most awe inspiring is the voluminous dining room that descends into the expansive living room, which is set off by beamed ceilings and concrete columns, all privatized by leaded glass windows. French doors open to a terrace that overlooks almost the entire Los Angeles basin.

I had the opportunity to study in person the 1923-1925-built, 2,884-square foot Samuel & Harriet Freeman House (1962 Glencoe Way – on the left) during my USC School of Architecture Heritage Conservation Course. The two-bedroom, one- bath home (also constructed using Wright’s textile block method) was originally designed as a salon space centered by a hearth with a semi-open kitchen plus roof decks and terraces. It could be considered the most endangered Wright site in Los Angeles: the experimental concrete blocks molded and poured on site did not last in the city’s unforgiving environment. However, like all Wright’s work, there’s an undeniable wow factor found in the unique hillside construction and the main living space’s signature, transparent, diagonal glass corners that take in vast city views.

I had the opportunity to study in person the 1923-1925-built, 2,884-square foot Samuel & Harriet Freeman House (1962 Glencoe Way – on the left) during my USC School of Architecture Heritage Conservation Course. The two-bedroom, one- bath home (also constructed using Wright’s textile block method) was originally designed as a salon space centered by a hearth with a semi-open kitchen plus roof decks and terraces. It could be considered the most endangered Wright site in Los Angeles: the experimental concrete blocks molded and poured on site did not last in the city’s unforgiving environment. However, like all Wright’s work, there’s an undeniable wow factor found in the unique hillside construction and the main living space’s signature, transparent, diagonal glass corners that take in vast city views.

Also in the Hollywood Hills, the John Storer House (8161 Hollywood Blvd., built in 1923) is a finely restored example of Wright’s concrete block construction. Film producer Joel Silver oversaw its multi-year restoration and even added a previously un-built pool after Wright’s design. The three-bedroom, three-bath, 2,967 square foot residence features (by today’s standards) quite small bedrooms but the soaring living room and multiple types of patterned block combine for a singular home. It remains privately owned and last sold for $6.8 million in 2015.

The Millard House in Pasadena (645 Prospect Crescent, known as La Miniatura) is Wright’s most successful concrete block project. There was no rebar used in the construction, so unlike Wright’s other experimental textile block homes, these blocks remained in relatively good condition. There are four bedrooms, four baths in 4,230 square feet of geometrically arranged living space defined by soaring ceilings, narrow windows and again, easy access to the outside via terraces and balconies. Set in a leafy ravine, the house overlooks a small lily pond and is on the National Register of Historic Places.

Wright’s final residential commission in Los Angeles was built in 1939 for George D. Sturges  under the supervision of John Lautner. It’s quite unlike Wright’s other Los Angeles residences: the modest, redwood-and-brick two-bedroom home is an example of his “Usonian” style and cantilevers out over its Brentwood hillside location. The interior features an open plan layout and at 1,200 square feet, it is indeed compact. The 21’ long redwood-clad deck brings the outside in. It is easily viewed from the street (449 N. Skyewiay Road) and remains a private residence.

under the supervision of John Lautner. It’s quite unlike Wright’s other Los Angeles residences: the modest, redwood-and-brick two-bedroom home is an example of his “Usonian” style and cantilevers out over its Brentwood hillside location. The interior features an open plan layout and at 1,200 square feet, it is indeed compact. The 21’ long redwood-clad deck brings the outside in. It is easily viewed from the street (449 N. Skyewiay Road) and remains a private residence.

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link